Humans may make do with one stomach, but not everyone takes the same approach to digestion. Consider this: The ruminant digestive system features a stomach with four compartments. What exactly is a ruminant? How does their digestive system work? What can you do to protect the health of a ruminant’s digestive system?

Identifying Ruminants

As Mississippi State University Extension explains, a ruminant is a cud-chewing hoofed mammal with a unique digestive system that includes a stomach with four parts.

This complex system lets it generate energy more efficiently from the consumption of fibrous plants when compared to herbivores with monogastric digestive systems. In other words, it gives these animals a very real edge by allowing them to thrive on foods that other animals would find lacking. Cattle, sheep, goats, deer, elk, giraffes, bison, and antelope are all ruminants.

Breaking Down the Ruminant Digestive System

Understanding the basics of how a ruminant’s digestive system works can help you keep the animals in your care healthy and productive. The University of Minnesota Extension offers plenty of useful information about the ins and outs of the ruminant digestive system.

The Mouth

While the star of the ruminant’s digestive system is the four-part stomach, the process actually gets its start in the mouth. Chewing stimulates saliva production, and a ruminant’s saliva plays a key role in the digestive process. For starters, it contains enzymes that help to break down fats and starches.

In addition, saliva serves as a buffer in parts of the stomach. The saliva mixes with the plant matter and makes its way down the esophagus when the animal swallows.

The Esophagus

Muscle contractions move food through a ruminant’s esophagus, and bidirectionality is the feature of interest here. The muscles of the esophagus can move food either down from the mouth or up the same channel from the stomach.

The Stomach

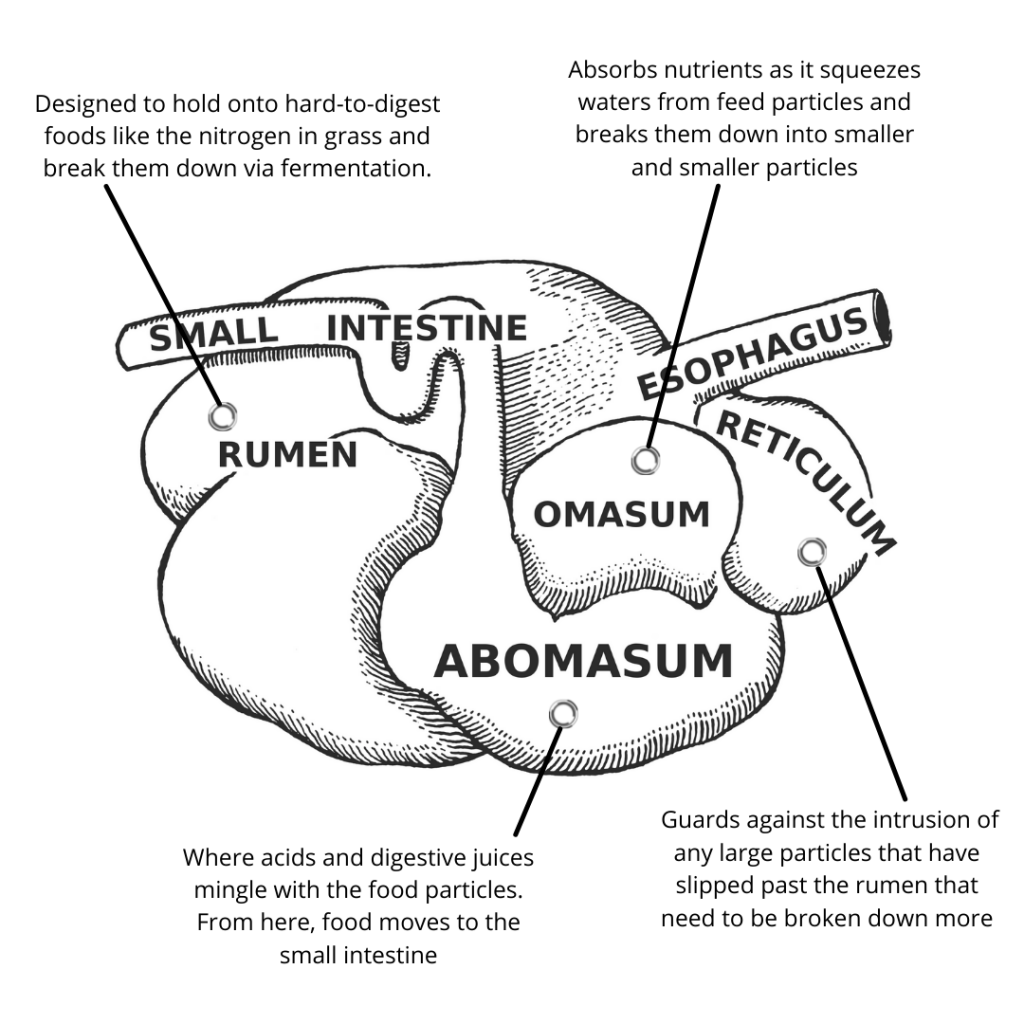

If the ruminant digestive system has a distinguishing feature, it’s clearly the stomach. As Purdue University explains this complex organ has four parts:

The rumen

The first part of the stomach, the rumen is also the largest compartment. It can store up to 50 gallons of material. However, it’s not just about storage. The rumen is designed to hold onto hard-to-digest foods like the nitrogen in the grass and break them down via fermentation and high concentrations of bacteria often dubbed “rumen bugs.” If roughage is proving especially difficult, the rumen extends its digestion time by encouraging further mechanical breakdown.

Using the bi-directionality of the esophagus, already swallowed food, or cud, is sent back to the mouth to be re-chewed for a while. Then, it’s re-swallowed and redigested. Have you ever wondered why ruminants belch? It’s to clear the gas produced by the fermentation that is part of their digestion.

The reticulum

Often called the honeycomb because of its appearance, these bands of muscle guard against the intrusion of any large particles that have slipped past the rumen that need to be broken down more before they go deeper into the stomach. If it discovers them, it forces them back up so that they can be chewed again. Unfortunately, cows and other ruminants aren’t always picky eaters. What happens when they ingest hardware like nails or baling wire? It tends to end up in the reticulum. In some cases, surgery may be required to save the animal. Otherwise, sharp hardware could pierce the stomach.

The omasum

The third section of the stomach is comprised of folds of muscles called plies. The multitude of layers increases the surface area, which gives the omasum more opportunities to absorb nutrients as it squeezes water from feed particles and breaks them down into smaller and smaller particles.

The abomasum

Known as the true stomach because it’s most like a monogastric animal’s stomach, the abomasum is where acids and digestive juices mingle with the food particles. From here, food moves to the small intestine.

The Small Intestine

The small intestine isn’t exactly small. It measures about twenty times the length of the animal and is made up of three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Most of the actual nutrient absorption takes place here. Nutrients are collected within the small intestine by the finger-like villi and released into the blood and lymphatic systems.

The Cecum

The cecum is a pouch that sits between the small and large intestines. Its purpose is a mystery, but it helps to break down any fiber that remains undigested.

The Large Intestine

The large intestine absorbs water. Microbes that live here also digest some feed. Then, the organ eliminates any undigested food as waste.

Keeping The Ruminant Digestive System Healthy

Keeping a complex system functioning smoothly can be tricky. Pro Earth Animal Health offers a quick overview of some common digestive problems:

- Acidosis – A metabolic disease that can be triggered by stress, illness, and other factors, acidosis causes shifts in the pH of the rumen that prompt the animal to decrease its food and water intake. If action isn’t taken to halt the disease process, the good bacteria in the rumen die off, toxins are released, and the animal’s immune system will continue to weaken. Acidosis can be fatal if the animal isn’t coaxed into eating and drinking.

- Rumen impaction – Without enough hydration, indigestible materials can pile up in the rumen. Handlers need to ensure that animals have access to clean water and are drinking sufficient amounts

- Hemorrhagic bowel syndrome – There’s no clear cause of HBS, but it tends to be the result of a blood clot or blockage in the small intestine. Taking steps to keep the rumen healthy seems to be the best way to prevent the issue.

Digestive health is an important part of an animal’s overall health. Understanding how the system works can help you make smart decisions about feed and care, including extending your growing season.

In addition, catching signs of digestive distress early makes finding an effective solution easier and more affordable. Be on the lookout for animals that are refusing to eat or drink, suffering from weight loss, lethargy or diarrhea, or are behaving unusually.