Forage is a cornerstone of both beef and dairy production. It’s the most basic and essential fuel for the cow’s growth, health and production. As such, we understand that quality is no small matter when choosing the best forage for cattle.

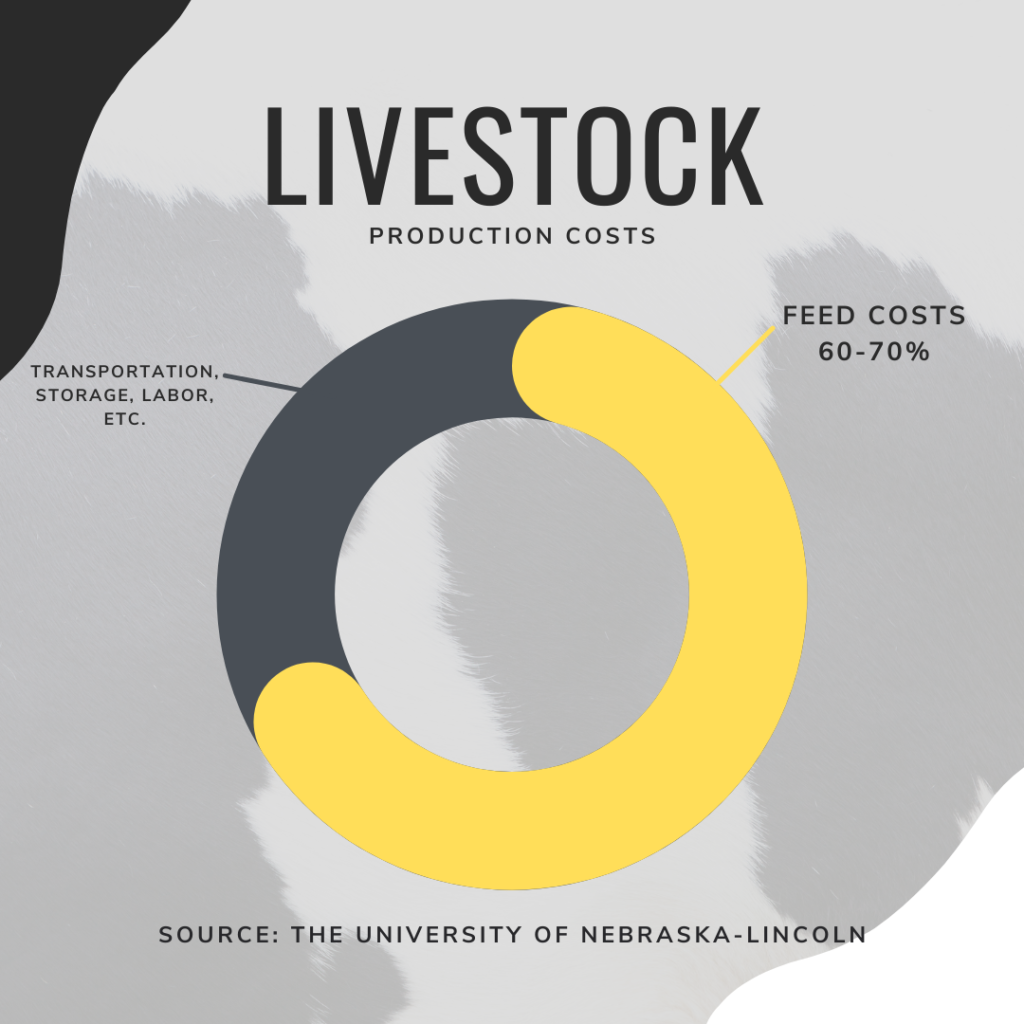

With feed costs representing anywhere from 60 to 70% of total production inputs according to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, better or worse quality could quite literally make or break the business.

While there are many different ways forage can be harvested, stored and fed, its production ultimately begins in the same place – the soil. And when farmed and managed responsibly, forages are not only a great feed for livestock, but they will also provide long-term health and fertility to the soil.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, 95% of all our food comes directly from the soil. This includes the fruits and vegetables we eat as well as what is consumed by livestock to create end products.

Cattle are in a unique position because by growing their forages – especially in the case of pastures and hayfields – the soil can be enhanced.

Plants are a lot like solar panels – they take in natural energy from the sun and convert it into nutrients that can be used as a fuel or energy source for the animals consuming it. When a cow eats a mouthful of grass or legumes, her rumen microbes will feed on it creating the fuel that builds muscle, supports growth, and allows for reproduction, milk production and much more.

All forages are very different regarding what nutrients they provide for animals. Not only is feeding suboptimal quality inefficient and not cost-effective, it’s also environmentally unsustainable. Remember, poor forages will use more resources in the growing and feeding compared to high-quality ones. Not to mention the challenges in keeping the ruminant’s digestive system healthy.

What’s In Forage, Anyway?

Deciding on the most appropriate type and variety of forage to feed cattle will depend greatly on region, seasonality and stage in production or lifecycle. Fortunately, there are many ways these can be mixed and matched to provide the most optimal diet for your animals.

The two broad categories forages are broken into are cool season and warm season. These are directly correlated to the time of year they are most prolific.

Cool season varieties are especially important as they play integral roles in fall and winter feeding. While they can be more difficult to maintain and expensive to upkeep, these cool-season types can help cut down on costly winter feedstuffs.

One of the benefits to cold season varieties is that they can be overseeded on top of warm season types to allow for an earlier spring and/or longer summer grazing season.

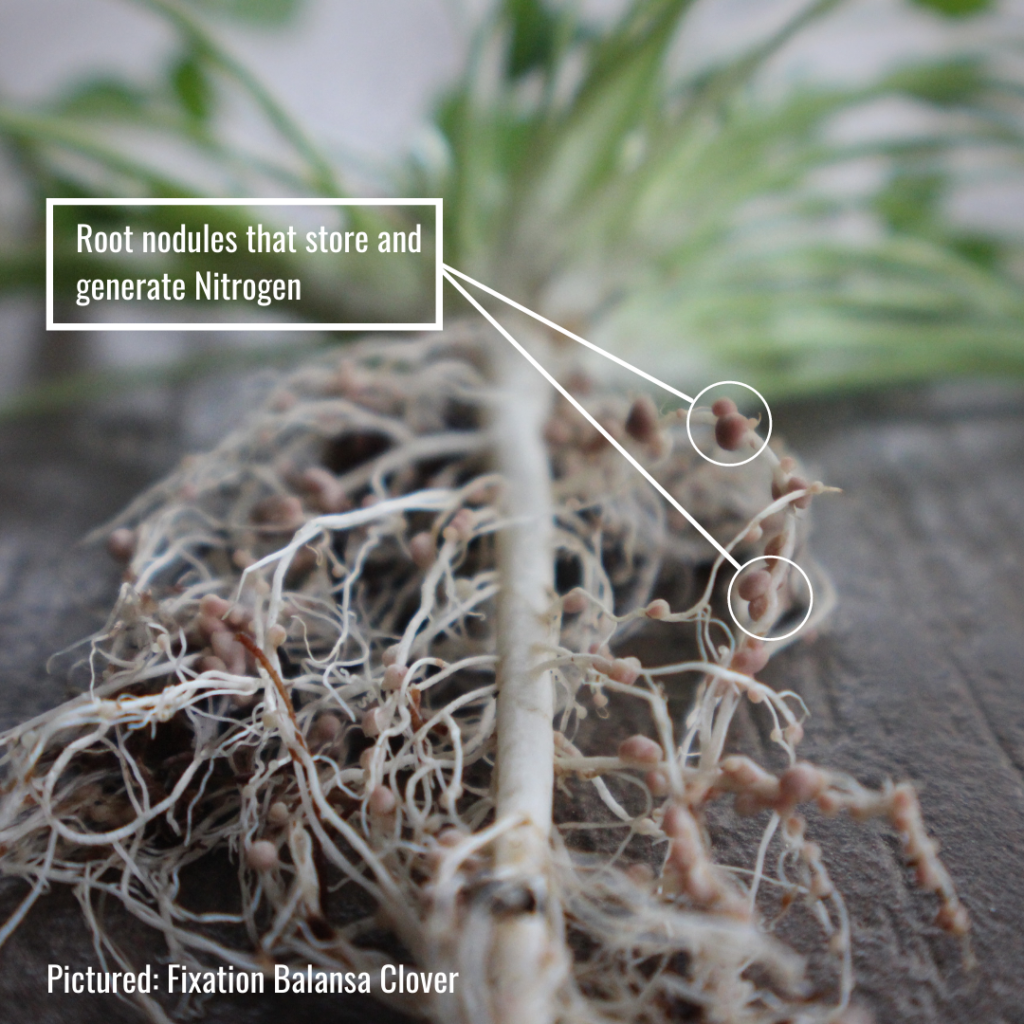

While there are many nutritious grasses, cool season legumes are especially worth noting. Legumes plants belong to the Fabaceae family. Not only are many of them nutrient-dense, but they also have a special symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria thanks to structures in their roots called nodules. This makes them an integral part of soil health and crop rotation programs.

Some of the most well-known legumes in the cattle world are alfalfa and clover. These grow very well with many other grasses. And, because many legume varieties are quite dense, growing enough of them can help cut down on unwanted weeds while boosting soil integrity.

Discover how to suppress weeds with cover crops in your pasture.

What’s The Most Nutritious Grass For Cattle?

Obtaining the proper nutrition from forages is a pivotal component, but its efficiency and profitability also cannot be overlooked. Harvested and stored options including hay and silage can certainly provide all the nutrition as a pasture can, but there is a serious cost associated with that compared to grazing where animals can “self-harvest.”

There are many variables and factors to this economic outlook, but the difference is significant according to a white paper by Kenny Burdine, an extension economist for the University of Kentucky.

When hay is stored and fed, there is always a loss associated with wastage or damage. Burdine calculated the difference at a 15%, 25% and 35% loss when feeding hay to cattle, each equivalent to the quality of the tonnage.

By his calculations, hay fed at a 15% loss worth $80 a ton cost $1.41 per ton with the assumption each animal consumed 30 lbs. per day. Contrast that to a pasture with a two acres per head stocking density – even with a $50 an acre maintenance cost per year, the cost of feeding would only be $0.42 per day.

Now, when discussing forage value and economics, one must also discuss how well it can be managed and produced in a specific region. Many specific varieties are quite well adapted to certain regions making it a good idea to stick to those that are tried and true. Likewise, growth distribution – meaning how a variety will proliferate after its establishment – need to be considered and how it relates to seasonality.

Other points relevant to the bottom line are quality, yield and persistence as explained by Steve Orloff and Dan Putnam of the University of California-Davis.

Potential use is also something producers should be aware of. For example, some pasture mixes are hardy enough to withstand hoof traffic and prolific enough to be converted to a hayfield and harvested. Other mixes (like alfalfa) are insufficient at withstanding grazing pressure and need to be harvested before feeding.

Quality factors And Detractors

There are a lot of factors at play that can help or hinder forage growth, production and quality. But there is one key overarching player to always be aware of – soil health.

You could say that the health and wealth of any crop, ultimately, begins quite literally at the roots and the soil surrounding them. This is why maintaining and preserving the soil in tandem with forage production is critical.

Soil is quite delicate. The earth only has about 60 years-worth of viable topsoil, according to Maria-Helena Semedo of the UN’s FAO, to support ongoing agricultural efforts without proper care and preservation.

Globally, soils are being degraded far faster than they can be replaced. A 2006 study from Cornell University published in the Journal of the Environment, Development and Sustainability found that, specifically, soils in the United States are degrading at a rate 10 times faster than they are being replaced. In China and India, that rate is about 30 to 40 times faster.

When we consider that, according to the Eniscuola School of Energy and Environment, it takes 200 to 400 years for a single centimeter of topsoil to be formed in most climates, the reality becomes very serious.

Research, such as work done at the University of California-Davis, has found that in addition to harming fertility, poor soil leaves plants more vulnerable to disease and pests while having an overall lower yield.

Using Legumes For Soil Health

Part of preserving soil is understanding it – what makes it healthy or unhealthy? Many forage growers and cattle producers may not know the specific metrics they are looking for.

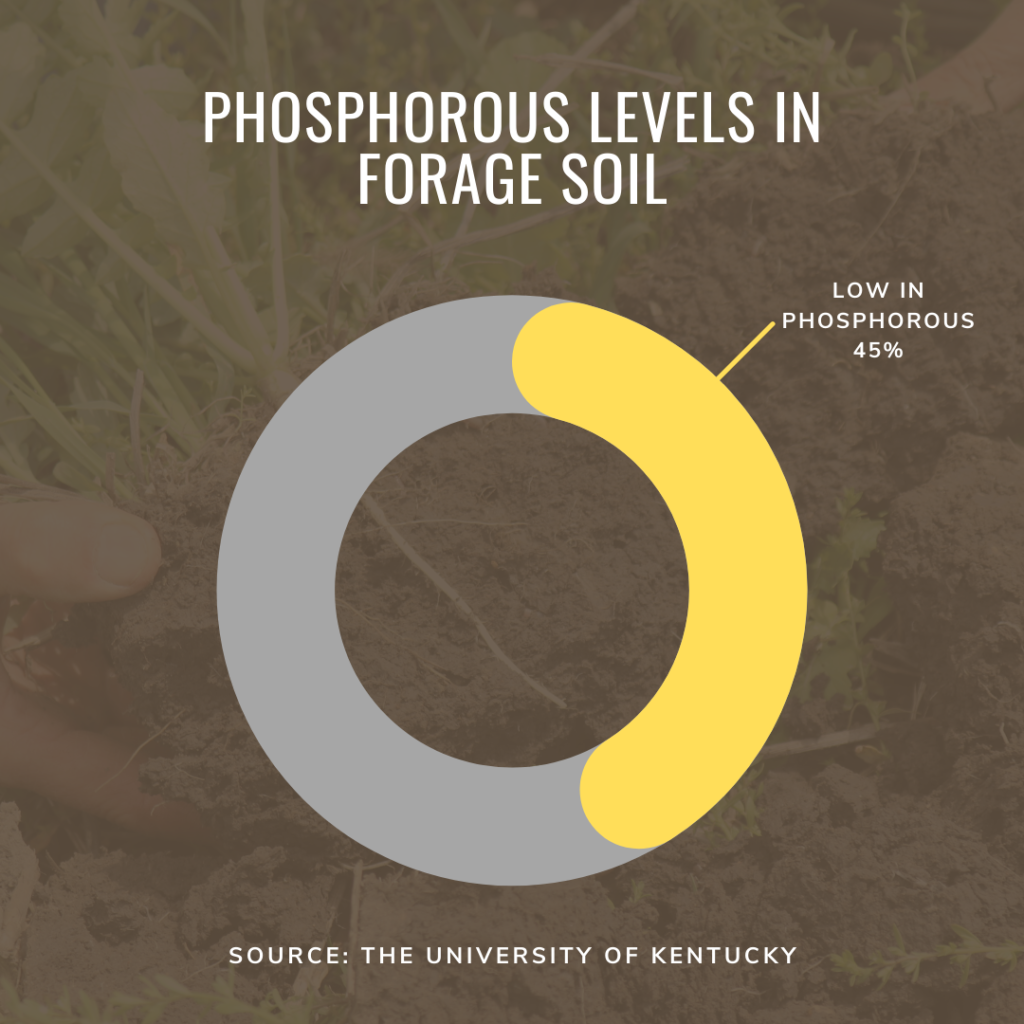

Only about 10% of all land used to grow forage is soil tested, according to the University of Kentucky. Of that, 45% is low in the essential nutrient phosphorous and 35% is low in the essential nutrient potassium.

And, interestingly, legumes – who are can help recycle nutrients according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service – are only grown in about one-third of the areas they could potentially be grown in.

Additionally, legumes can also enhance soil organic matter, improve soil structure and lower soil pH – much of this is due to the Rhizobia bacteria that live in the nodules of their roots. These bacteria are what allow them to fix their own nitrogen.

Having a significantly different background compared to other forage types, planting legumes can also enhance overall biological diversity which, in turn, can help break harmful pest cycles including diseases, weeds and insects in a crop rotation.

Know Your Resources

The first step to incorporating legumes is to do an annual soil check. After all, planting, harvesting and forage equipment is typically checked at least once a year – soil should be treated no differently! Soil requires management much like anything else in farming. And, of course, you can’t manage what isn’t measured.

An agronomist can help make some recommendations based on specific soil test results, and help accommodate a forage plan to a specific farm. Like so many other things in our agriculture system, one of the best ways to learn is from other farmers who share their own experiences in a similar region and/or livestock management system.

There are also lots of academic resources available to help develop a healthy forage plan. These include your local extension service, Natural Resource Conservation Service, the National Hay Association and the National Alfalfa and Forage Alliance.