In part one of this three-part series on the economics of cover crops, we explore how to reduce farm inputs.

“Yeah, the principle of cover crops makes sense but how much are they going to cost me?”

From farmers using them in rotations to field experts alike, this is one of the most common questions they get asked when discussing the integration of cover crops. And in a business where inputs can quickly get out of hand and cut into thin profit margins, it is understandably so.

According to Jerry Hall, President of GO SEED, this question needs to be flipped on its head with farmers asking, “How much can cover crops save me?”

“With strategic use, cover crops can help decrease inputs like fuel and labor, while providing long-term production benefits from resource improvement,” explains Hall. “To see the full potential, they bring to an operation, we need to stop chasing yield and look at the overall production picture. That’s where we’ll see the real savings.”

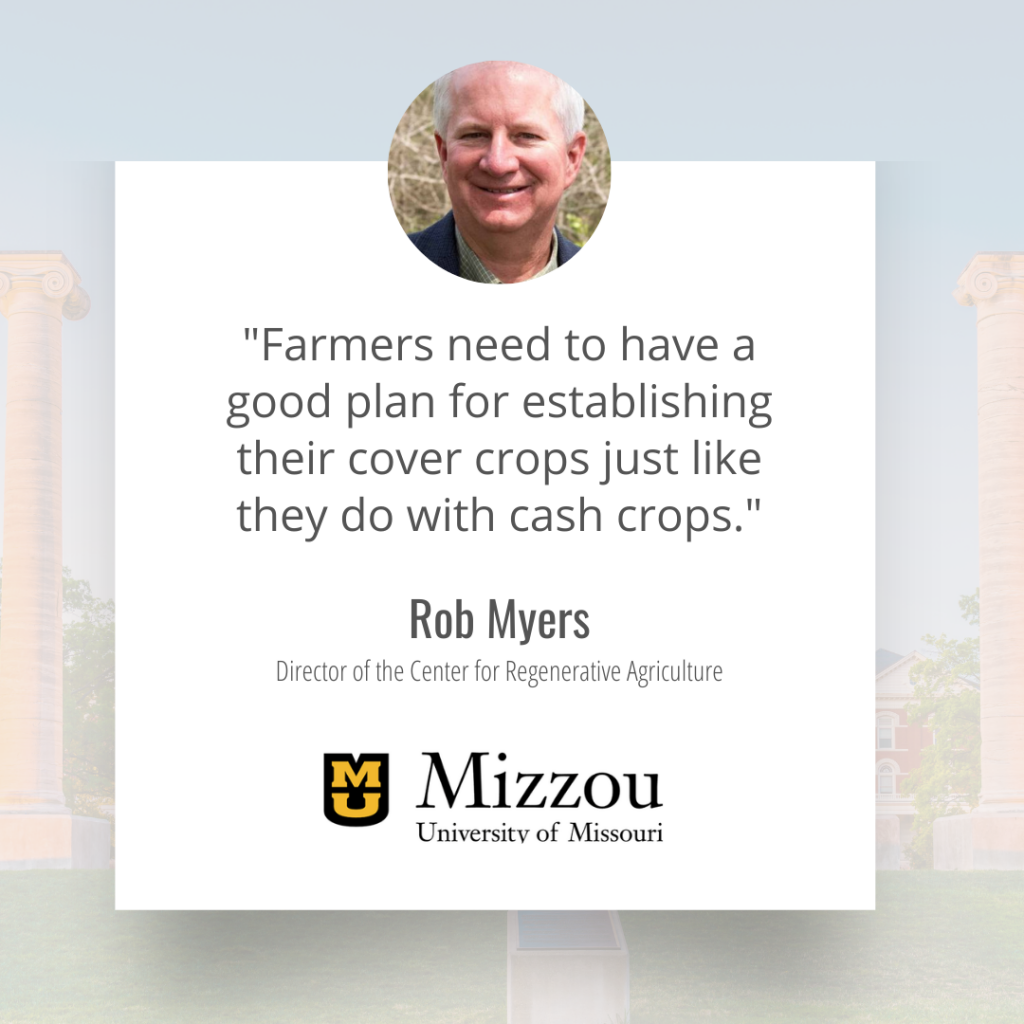

But putting cover crops in the ground isn’t an automatic ticket to financial success, with cost considerations of the cover crop itself needing to be kept in check, adds University of Missouri’s Rob Myers, Director of the Center for Regenerative Agriculture and Ray Massey, Extension Professor in Agricultural and Applied Economics.

Below, they discuss how farmers can considerably reduce inputs with cover crops while also reducing inputs related to cover crop production.

Equipment-Related Expenses

Something to pay special attention to when using cover crops is how much is being spent on all equipment-related expenses.

“If the cover crop doesn’t grow, throwing the seed out there is really just burning money,” says Myers. “Farmers need to have a good plan for establishing their cover crops just like they do with cash crops.”

This means cover crops need to be seeded at the right time with the right equipment for the cover crop species being used. To ensure adequate distribution, the drill or row planter needs to be checked and calibrated to ensure seeds have the best soil contact possible.

“Broadcasting cover crop seed can also work,” Myers adds, “but it’s not a good idea with larger cover crop seeds or really late in the fall when there is little time for a rain to come.”

Extension Professor in Agricultural and Applied Economics Ray Massey, at the University of Missouri, says there are some hidden equipment costs that farmers need to be aware of as well. For example, he recently spoke with his farmer who assumes a $7 an-acre custom rate for planting while figuring his own equipment is more efficient at about $5 an acre. But that $5 charge doesn’t necessarily account for all the costs of equipment.

“People look at cost differently,” Massey explains, “things that people experience or feel (differently) is cash cost.” All farmers consider fuel to be a real cost of putting in a crop. However, some farmers ignore their own labor or the depreciation of their equipment.

“I encourage producers to recognize all costs.”

On the flip side, there are equipment-related savings to be had by integrating cover crops into a no-till type system, says Hall, especially when it comes to fuel.

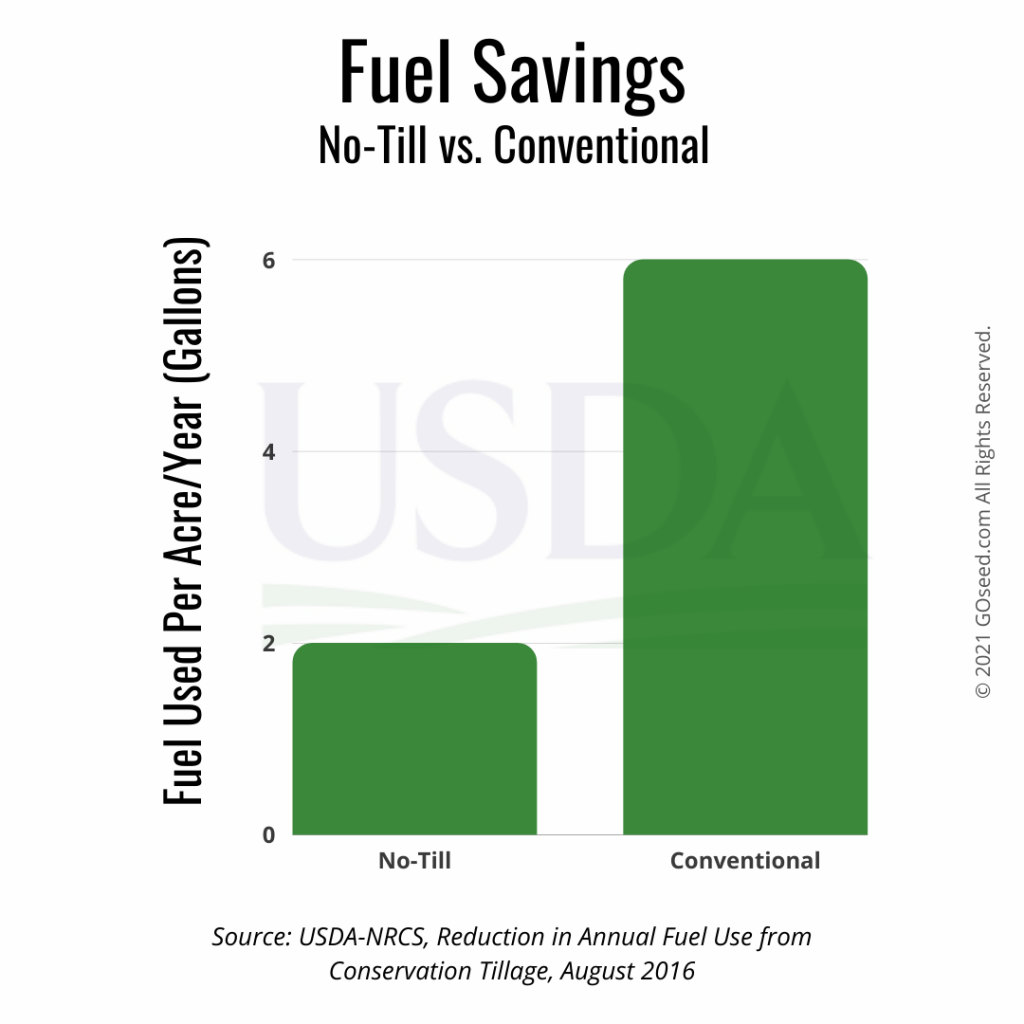

A recent analysis by the Natural Resource Conservation Service and Conservation Effects Assessment Project compared gallons of fuel used in seasonal and no-till systems with fuel consumption in conventional tillage systems. This looked at farms across the continental US, breaking them into 10 different regional locations.

“On average, conventional tillage was found to use more than six gallons of fuel per acre each year, while no-till used two gallons of fuel per acre each year,” explains Hall. “As of mid-August, the average price of diesel is $3.18. For someone farming 1,000 acres, going to a no-till system has a cost savings of $12,720 per year on fuel alone.”

Reduce Farm Inputs: Feed Potential

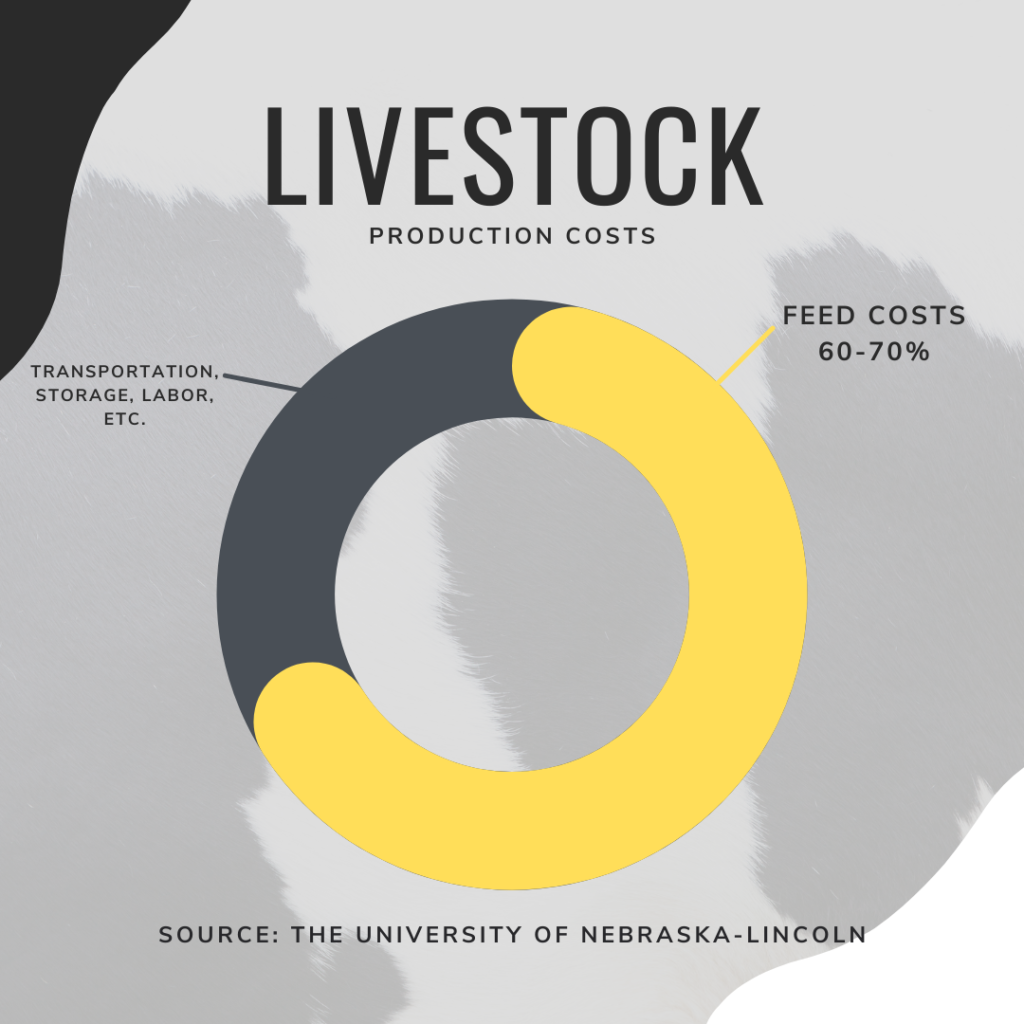

For livestock producers, using animals to harvest cover crops rather than equipment has huge cost savings. With the right feed quality, they can also cut huge chunks out of the feed bill.

Feed costs tend to encompass 65-75 percent of a livestock operation’s feed budget. When utilizing grazed forage, producers can save 10-20 percent of that cost of production.

Nearly 20 years ago, 50 percent of Double J Jersey’s feed budget for the Monmouth, Ore., farm was spent on feed costs.

“We’d taken an operating loan out to buy alfalfa for winter feed. I knew that if we ever wanted to get out of debt and create the opportunity for the next generation to come back to a thriving business things had to change,” recalls the farm’s owner Jon Bansen.

Working with GO SEED, Bansen overhauled his forage production to maximize grazed feed.

While the sweet spot for making money is to have 50 percent of all feed consumed as grazed forage, Bansen has pushed it even further with 90 percent of feed coming from grazed forage for six months of the season and the early and later edges sitting at 60 percent.

This was achieved by establishing mixtures with upwards of 10 different species of grasses, forbs, herbs, and legumes and putting cows on a 30-day rotation. Rather than grazing covers tight for increased forage quality, Bansen leaves five inches of covers to support soil health and lock in moisture.

As a result, the only bought-in feed costs the farm currently has are a few loads of alfalfa each year and carrot pulp that cows receive to encourage them into the milking parlor.

However, to capture these savings, the right varieties and grazing methods must be utilized. There are also infrastructure considerations to be had.

“Cover crops can be a good way to provide extra forage on a farm,” explains Myers. “If water and fencing are already available, grazing cover crops can provide a profitable return in the first year.”

Another reason more farmers are using cover crops is that they are seeing the benefits of using cereal rye to help control herbicide-resistant weeds. Rye can also function as part of a field’s overall weed management strategy; the rye will typically still be used in combination with herbicides, but potentially the total cost of the weed control program may be less.

“Overall having a strategy for how the cover crops fit into the field management plan can help lower input costs and provide modest yield boosts over time,” Myers continues. “Not necessarily in the first year of use but as soil health improves.”

Growing Costs

Like any other crop, cover crops will require some degree of growing costs.

For soils that are highly compacted, Myers recommends deep-rooted types that can penetrate such as radishes.

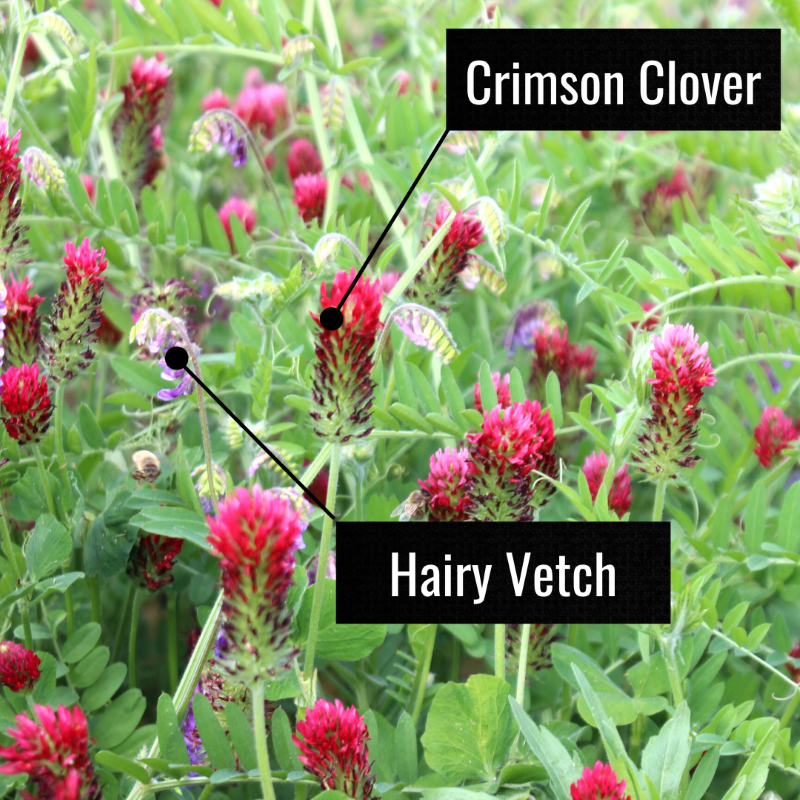

In soils with fertility issues, legumes like crimson clover or hairy vetch can do well and help restore the soil.

“In a national cover crop economics review we did through the USDA-SARE program, we determined that it takes cover crops an average of three years to break even, then after that, they provide a profitable return in subsequent years,” he explained. “This means that in the majority of farm situations, there is an investment cost in the first couple of years. Farmers need to have a multi-year perspective.”

One common mistake is not paying attention to residual herbicides that have been on a field, Myers says. Herbicides that were put in advance may be strong enough to kill a cover crop, particularly Brassicas and some of the legume cover crops; grasses such as cereal rye or triticale are less affected.

“It’s important to review what chemicals have been sprayed on a field and how it might impact relevant cover crops,” says Myers.

But used correctly, cover crops can decrease certain input costs associated with growing a crop. This comes down to variety selection and management practice, adds Hall.

“Rather than leaving fields bare post-harvest, establishing a rapidly growing cover crop is going to out-compete weeds, reducing pressure on the subsequent crop,” he says.

In work done by USDA-SARE looking at conservation tillage systems in the southeast, it was found that planting a rye cover crop in Mississippi reduced total weed biomass by 19-38 percent across different tillage systems and total weed density by 9-27 percent.

Heavy hitting legumes bred specifically to fix high amounts of nitrogen can also make a dent in fertilizer costs, notes Hall.

“Legumes are signature for forming root nodules from rhizobia bacteria which pull in nitrogen from the atmosphere as a nutrient resource for the plant to grow. Root nodules also release nitrogen into the soil as an available nutrient for companion and succeeding crops. However, the real magic happens as the legume ends its lifecycle, releasing nitrogen into the soil as components of it begin to decompose,” says Hall.

In a trial conducted at the Ewing Demonstration Center (EDC) in Illinois, decomposing FIXatioN Balansa clover added 269 pounds of nitrogen per acre over a period of six and a half months. In return, FIXatioN Balansa clover improved the soil nitrogen contribution and soil ammonium ppm by 40 percent and 80 percent in just four weeks after corn emergence (WAE).

While it adds to seed costs, legumes quickly pay for themselves in the amount of nitrogen added to the soil which is immediately available to succeeding crops. Data from the EDC trial shows FIXatioN Balansa clover fixed 50 pounds of nitrogen per acre at 4 WAE. Based on a rate of $0.60 per pound for nitrogen fertilizer, this is a cost savings of $30 per acre. At 10 WAE, 84 pounds of nitrogen per acre was fixed for a cost savings of $50.40 per acre. [LW1]

Time Resource

From a time resource point of view, how cover crops play into the farm’s calendar is another point of economic significance. For example, Massey says killing a cover crop is usually left to the busiest time of the year.

“You will want to spend time on a pre-emergent or pre-plant application of an herbicide that isn’t in any way adding to your fieldwork activities,” explains Massey.

“From an economic perspective, people value time according to time of the year,” he says. “If you’re not already doing that activity, particularly in the spring, it’s an additional cost because it’s not something you would normally do.”

When used to support a no-till system, this can be alleviated. In the same project that found no-till conservation systems to have a significant reduction on fuel use, it also found farmers saved around 67 hours of work per eliminated pass when working a 1,000-acre field at 15 acres per hour.

Think Big Picture But Outline What You Are Trying To Achieve

While the above outlines a few input-saving opportunities farmers may be able to achieve with the right adoption of cover crops, making a sustainable dent in operation costs is only going to happen if clear objectives are set and then worked towards, says Hall, Massey, and Myers.

“You really need to have a long-term strategy to reap the rewards. Think of it like using lime to raise soil pH – which can take upwards of three years to pay off – or buying new equipment,” says Myers. “Addressing specific goals, such as grazing or weed control, can help cover crops pay off more quickly – sometimes in just a year or two. But once cover crops have a chance to start improving soil health, that’s when we see bigger profit returns for long-term performance and resilience of the field.”

In part two of this three-part series, we will discuss the economic benefits of improved resources like soil health.