Are bees like livestock? Bees play an integral part in the food chain. Here’s how any agricultural system can create beneficial pollinator habitats.

From livestock feed crops like alfalfa and clover to produce like blueberries and melons, commercial production of more than 100 US-grown crops relies on bee pollination.

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), indicate pollinators affect 35 percent of global agricultural land, contributing between $235 – $577 billion a year to global crops directly relying on pollinators. A recent study from Rutgers University puts that figure at $50 billion per year in the US alone.

“Bees in particular are the most productive pollinators, serving as a key player in the food chain,” says Brent Jones, head of GO SEED’s Iowa Research Farm. “Yet in the last couple of decades, the bee population has significantly suffered, directly threatening global food production.”

According to the USDA, this decline is largely due to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), resulting in colonies abandoning immature bees and food supply. A wide range of factors such as diseases, nutritional deficits, habitat loss, and climate variability has been attributed to this. The intensification of agricultural production leading to the decline of crop diversity has also been attributed to CCD.

Lessons from a science teacher turned vegetable farmer turned beekeeper

Integrating cover crops with varying blooming dates and high nutritional content significantly improved the health of Cory Klehm’s bee colony. In return, his vegetable farm saw yield improvements due to the increased pollination.

Growing up on a conventional corn and soybean farm in Iowa, Cory Klehm kept his interest in food production as he pursued a fulfilling career as a teacher. Twenty-six years later, the present day finds him as the science teacher at Fairfield Middle School in the southeast part of his home state.

Fifteen years ago, Klehm and his wife, Shawn, purchased 24 acres of land to convert into an organic vegetable farm. With his background in conventional farming and a curiosity for science, Klehm wanted to try his hand at growing vegetables “as close as nature intended it” as possible.

“We started the vegetable farm to teach our three kids work ethic and introduce areas of education to their lives that only come with hands-on work from growing a crop and harvesting it to then selling it at a farmers market a couple of times a week,” he says.

With a specialty in heirloom produce, the family soon gained a local following for their produce, which includes zucchini, potatoes, garlic, and basil to name a few, with their tomatoes holding the most notoriety.

A few years into the enterprise, Jones was picking up an order of tomatoes for his family and asked Klehm about his soil health program.

“After taking soil samples and assessing the soil profile – we had some areas with compaction and a surprising variety of soil types for 24 acres – we started to do some test strips to try different cover crops, min-till and no-till to see what worked. We scaled it gradually to where the majority of the farm is in cover crops today and we’re trying our first year of interseeding vegetables into standing cover crops,” says Klehm. “Cover cropping has had an amazing impact on our soil, reducing ponding issues in areas that historically had poor drainage and improving the overall soil structure.”

As the vegetable enterprise took off and Klehm watched his three children, Corynn, Reese, and Khai, take away so many positive skills and experiences from their involvement, he saw another area of growth for his oldest son.

“My oldest was terrified of bees so when thinking of how to help him get over this fear, we enrolled together in a beekeeping class with the Southeast Iowa Beekeeping Association,” he says.

That spawned everything, says Klehm. Not only did his son overcome his fear of bees, but it would eventually benefit the farm’s vegetable output immensely.

Keeping the bees at home

Whenever a bee leaves its colony in search of food, it increases its risk of contracting a disease that it could bring back and wipe out the entire colony. It also opens the bee up for becoming exposed to crops that have been freshly sprayed which can be harmful. Wanting to reduce the amount of loss his colony was suffering and better reap the benefits of having bees on his own crops, Klehm realized he was going to have to find a way to keep his bees as close as home as possible. Jones and GO SEED had also been doing some research into cover crop management to support pollinator habitats and worked with Klehm to find a solution.

“The key to building a beneficial habitat for bees is to provide a constant food source which can be achieved by using a cover crop mixture with differing blooming dates so there was constantly something in bloom,” explains Jones. “On Cory’s farm, we fall planted a mix of annual clovers with different blooming dates and spring-planted crops like phacelia, buckwheat, and sunflowers to bloom after the annual clovers are done.”

To say it was a success is an understatement. Not only were the bees staying on the farm and not traveling for miles in search of food, but his crop yields were seeing the benefit of improved pollination. While Klehm notes he never created a thorough scientific trial with controls and variable measurements, anecdotally, he attributes the bees staying at home to a 30 percent increase in crop yield, with his tomatoes seeing the biggest benefit.

“At one point in time we had 3,000 tomato plants and were pulling 400-500 pounds of tomatoes every other day,” he says. “I’ve never seen plants with so many tomatoes. It was unreal.”

From a beekeeper’s perspective, the new approach was supporting the colony like never before.

“We had swarms three times, which only happens when your population is exploding so the bees divide themselves to start a new colony with a new queen. I had never had it happen before,” explains Klehm. “Along with the growing population, the colonies were extremely healthy and producing more honey in 30 days than my first hive did in a year.”

Treat bees like livestock

While crop diversity is important to provide bees with a continual feed source, the crop must also meet a bee’s nutritional requirements to keep it healthy and productive, says Jerry Hall, director of research for GO SEED.

“Bees need at least 20-25 percent pollen crude protein, with a colony consuming between 55-122 pounds of pollen per year, and have required values of 10 different amino acids,” explains Hall. “We need to think of pollinators more as livestock and plant ‘forage’ to match up to their needs from both a timing and nutritional quality. Not all pollen is of the same quality. Most often it will take more than one type of forage to provide all the nutritional needs.”

For example, sunflowers, what most would think is good food for pollinators, only have 13-19 percent crude protein, while the likes of Balansa clover, white clover, and hairy vetch average around 25 percent.

The game-changer for Klehm’s colonies was the introduction of high-protein clovers, which exceeded both crude protein and amino acid requirements, providing excess nutrition.

The success experienced at Klehm’s farm is not unique, with a 2016 trial by NRCS-CIG seeing success in the conservation of bee pollinators when integrating clovers into pastures in western Oregon.

Planting a mix of 22 different plant species at a rate of 4-5 pounds per acre across four ranches, trial, and control pastures were monitored every 1-2 weeks for two years. In the first year, 16 species of native bees were observed in the seeded pastures and only three in the control. The following year, 22 species of native bees were found in the seeded pastures and 10 were found in the control.

Integrating Pollinator Habitats Into Agricultural Systems

Whether it’s a vineyard, orchard, livestock ranch, or commodity crop farm, there is a lot of opportunity for any agricultural system to integrate pollinator habitats without disrupting the production of their main enterprise.

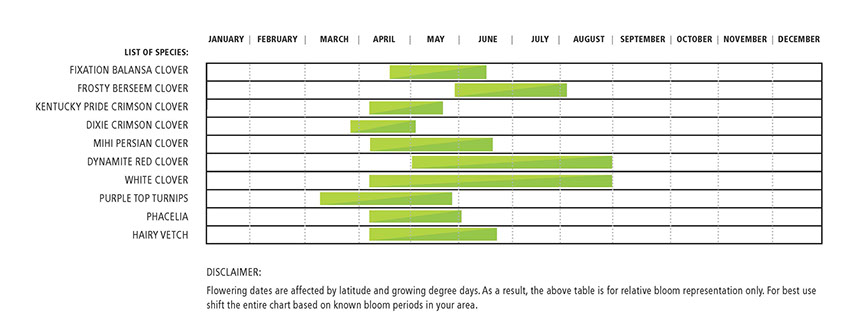

To identify which cover crop species are flowering in their area, Hall recommends producers start by making a chart (see Pastures for Pollinators example) that outlines blooming dates so mixtures can be planned to provide consistent feed.

“A great resource is pasturesforpollinators.com, which has a blooming chart of common cover crop species. While the dates of flowering can change from year to year based on climatic conditions, the order of flowering remains fairly consistent,” says Hall.

While it is essential for crops to reach maturity to provide pollinators with food, this may present a challenge to row croppers who need to terminate a cover crop before it goes to seed. Management of the pollinator crop also needs to be done with bees in mind, avoiding pesticides and limiting herbicide use.

“Some farmers may be able to let cover crops grow longer by planting early with strip-till or rows that winterkilled. Perennial clovers are also an option, with ongoing research on white clover showing potential,” explains Hall.

Management-friendly options include planting pollinator cover crops non/low productive land like gullies, terraces, borders, waterways, and woodlands.

“Creating productive pollinator habitats doesn’t have to disrupt your system or take up huge areas of land,” adds Jones. “Get creative and look at areas of your farm that could do better as something different.”

Opportunities available

For farmers and ranchers looking to improve pollinator habitats, there are several opportunities available. If they wish to host hives, a good first step is reaching out to local beekeeper organizations.

There are also several government-funded conservation programs through the likes of NRCS that can provide producers with funding.

“Pollinators play such an important role in the success of commercial agriculture and the world’s food production. No matter what type of system you operate, it is directly impacted by pollinators and directly impacts pollinators,” concludes Klehm. “No matter how big or small of an acreage you have, it is our responsibility as food producers and environmental stewards to support these vital organisms.”

Cover Crop Corner is a new educational column from forage application company Grassland Oregon and is free for print or digital distribution by media outlets. To be added to the distribution list, please email info@goseed.com