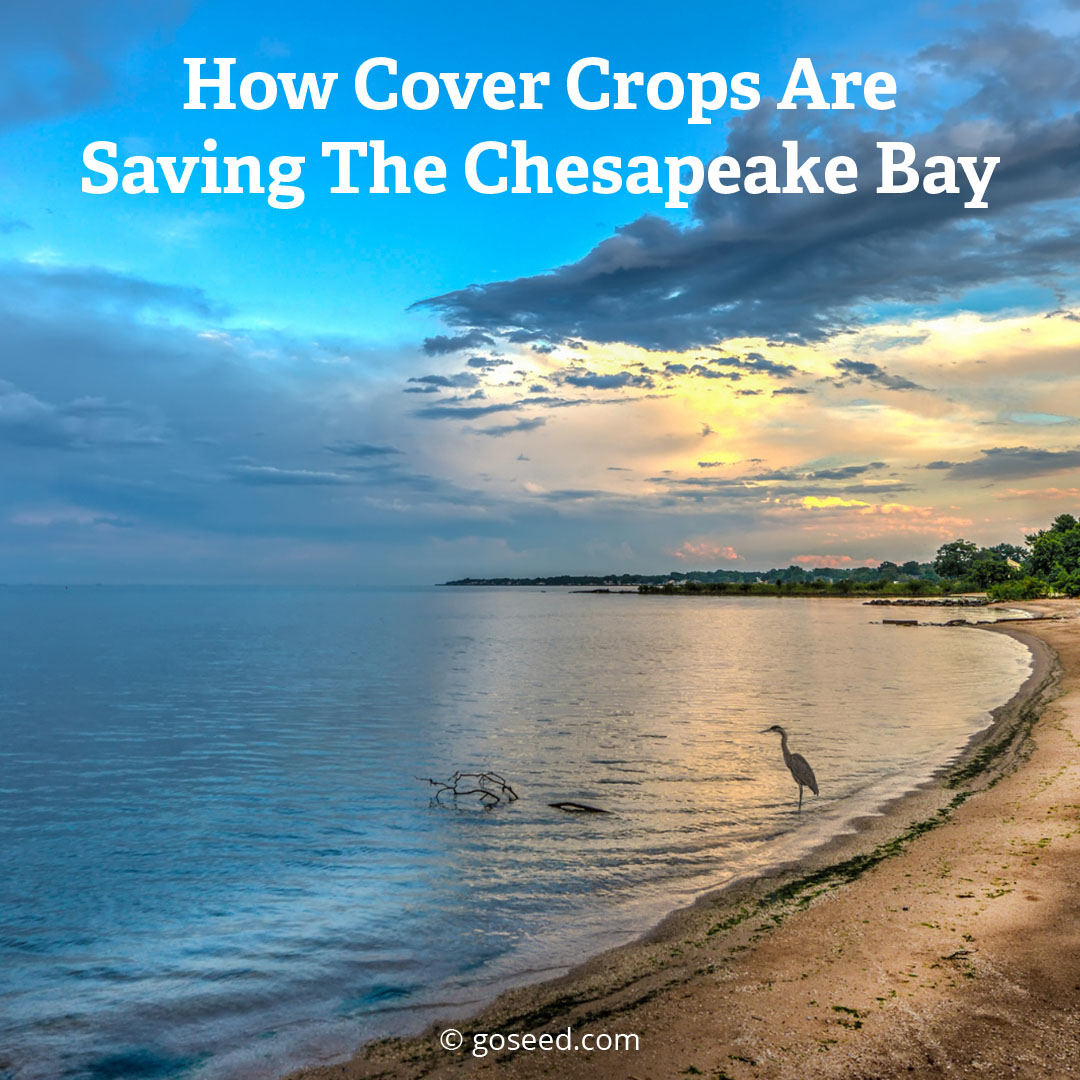

The Chesapeake Bay serves as a case study in how cover crops prevent nutrients from entering watersheds while also recycling them for future cash crops.

Cover crops are one of the simplest and most effective ways farmers can keep their fertilizer in place.

It’s why states like Maryland and Virginia pay farmers to seed cover crops to help keep nutrients out of the Chesapeake Bay. And as cover crop use has continued to grow in the watershed, the efforts of such incentive programs—and the farmers using them—are paying off.

“It’s a success story,” says Dr. Shannon Cappellazzi, GO Seed Director of Research. “There has been higher adoption of cover crops in that area because of some of the incentive programs. There have been positive outcomes to the health of the aquatic ecosystem of the Bay. It’s a combination, the policy is working, the producers are seeing the benefits for themselves, and the downstream ecosystem services are being taken care of.”

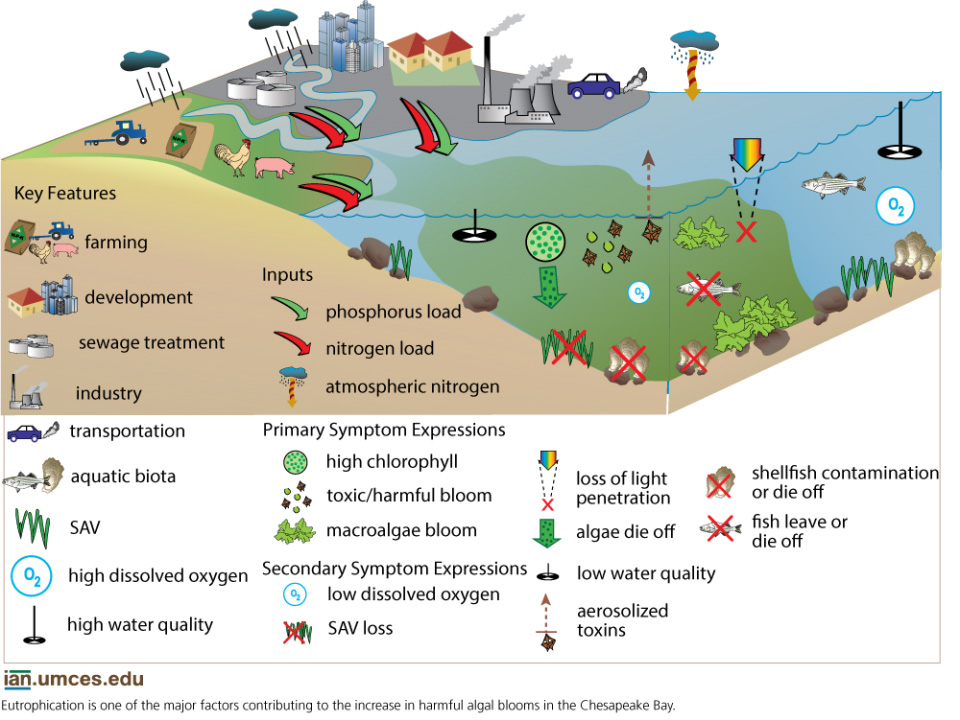

Nutrient Runoff Negatively Impacts Bay’s Health

The focus on cover cropping began after it was discovered that fertilizer runoff from farm fields negatively affects the water quality of the largest estuary in the U.S. According to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), agricultural runoff is the largest source of pollution to the Bay: roughly 40% of nitrogen and 50% of phosphorus entering the Bay comes from farms.

That runoff has dire consequences. Too much nitrogen and phosphorus feed algal blooms that create “dead zones”—parts of water where little to no oxygen exists, both stressing and killing sea life.

The pollution plaguing the Chesapeake Bay became so bad that in 2010, the EPA created a pollution diet for the watershed. Called the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), the EPA says this planning tool calculates the maximum amount of a particular pollutant a body of water can receive, while still meeting water quality standards. To stay below the TMDL, the Chesapeake Bay Program partnership agreed to have restoration practices in place by 2025, along with an Accountability Framework.

To achieve that 2025 goal, CBF says that Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania—the states that make up 90% of the watershed’s pollution—need farmers to make 52%, 77% and 93%, respectively, of their remaining nitrogen reductions.

One of the best ways to do that? Cover crops.

Cover Crops Help Halt Nutrient Losses

As Civil Eats reports, farmer and Wye Research Center scientist Kenneth Staver and his team were researching how nutrients moved from farms to the Bay, when they discovered a lot of nitrogen enters the groundwater during the winter.

Not all nitrogen fertilizer that is applied during the primary growing season is used by the target crop. The remaining nitrogen is transformed into nitrate that moves through the soil with water. Cover crops can step in to take that excess nitrogen out of the soil and stop it from moving out of the soil and into the water.

To confirm this, Staver and the former research scientist Russell Brinsfield studied rye winter cover crops planted after corn harvest. They found it consistently reduced annual nitrate leaching losses by approximately 80% compared to bare fields.

And under long-term continuous corn production, shallow groundwater nitrate-nitrogen concentrations decreased by at least half after 7 years of winter cover cropping.

As cover cropping has increased in the Bay watershed— as of 2020, about half of Maryland’s fields are cover cropped—the Bay has improved. The Chesapeake Bay Watershed model estimates that nitrogen loads are down by 11%, phosphorus by 10% and sediment by 4%.

And the most recent data from the USDA found that agricultural conservation practices, which includes cover crops, helped reduce the total amount of nitrogen and phosphorus entering the watershed from fields by 44% and 75%, respectively.

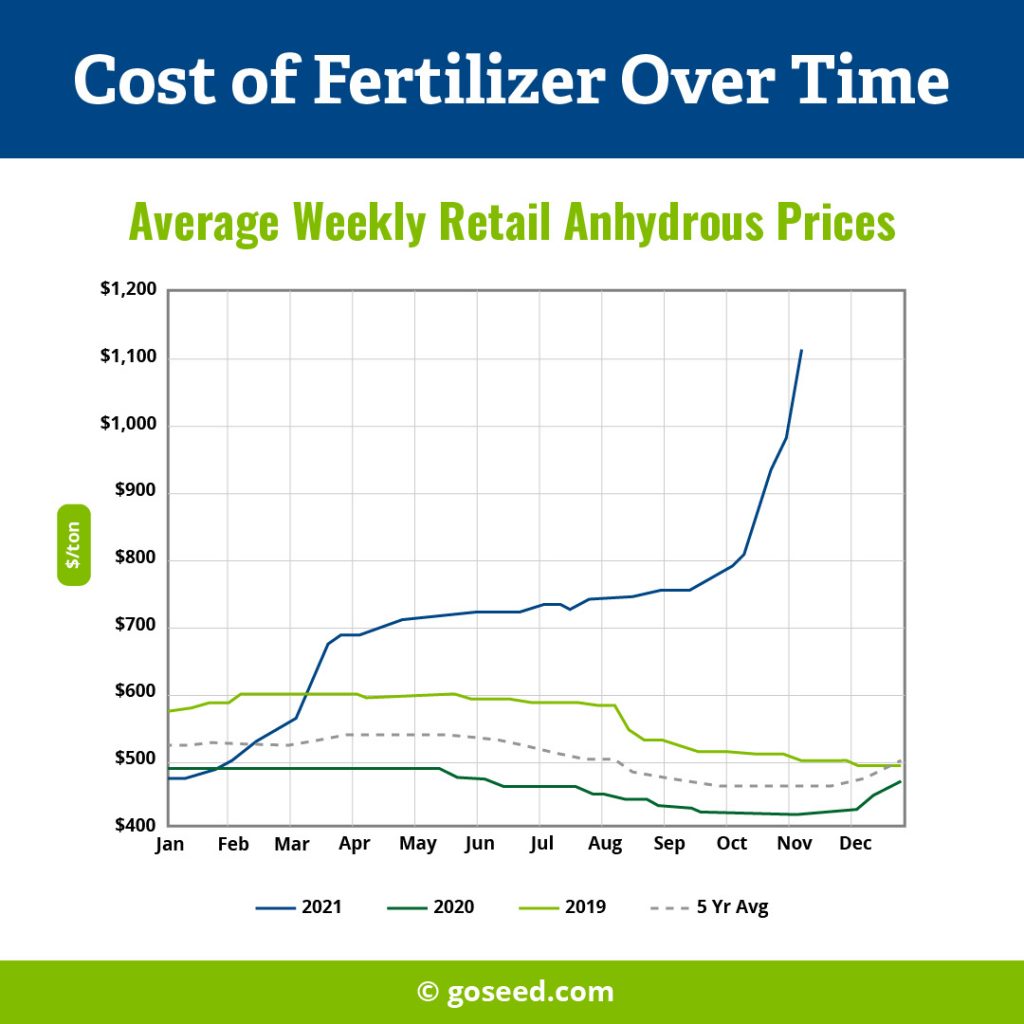

Preserving a Valuable Input

When nutrients leave the field, they’re not just harming the watershed. Farmers are also losing money on a high-cost expense.

Luckily, cover crops don’t just prevent nutrient loss. They recycle them and ensure they’ll be available for the next cash crop.

“Anytime you have a plant growing in the ground, there’s going to be carbon taken up through photosynthesis,” says Dr. Cappellazzi. “About half of that carbon is going to move down through the roots, into the soil, and will feed the microbial community. And when you feed the microbial community, you increase the rate at which nutrients are recycled, at which those nutrients become available to the plant.”

She adds that farmers can increase their soil nitrogen by growing a legume.

“You have this increased benefit of the legume’s association with rhizobia bacteria, allowing for nitrogen fixation,” she explains. “That’s taking nitrogen from the atmosphere, breaking those nitrogen bonds and making it into a form that’s available to the plant.”

We’re currently working on research to better determine how much nitrogen legume cover crops can provide and when it’ll be available for the cash crop. In the meantime, Michigan State University offers a nitrogen credit chart that provides an estimate of the amount of nitrogen different legumes can provide.

Farmers Save on Fertilizer Costs

Between nutrient cycling and fixing nitrogen, many farmers see a reduced fertilizer bill thanks to cover crops.

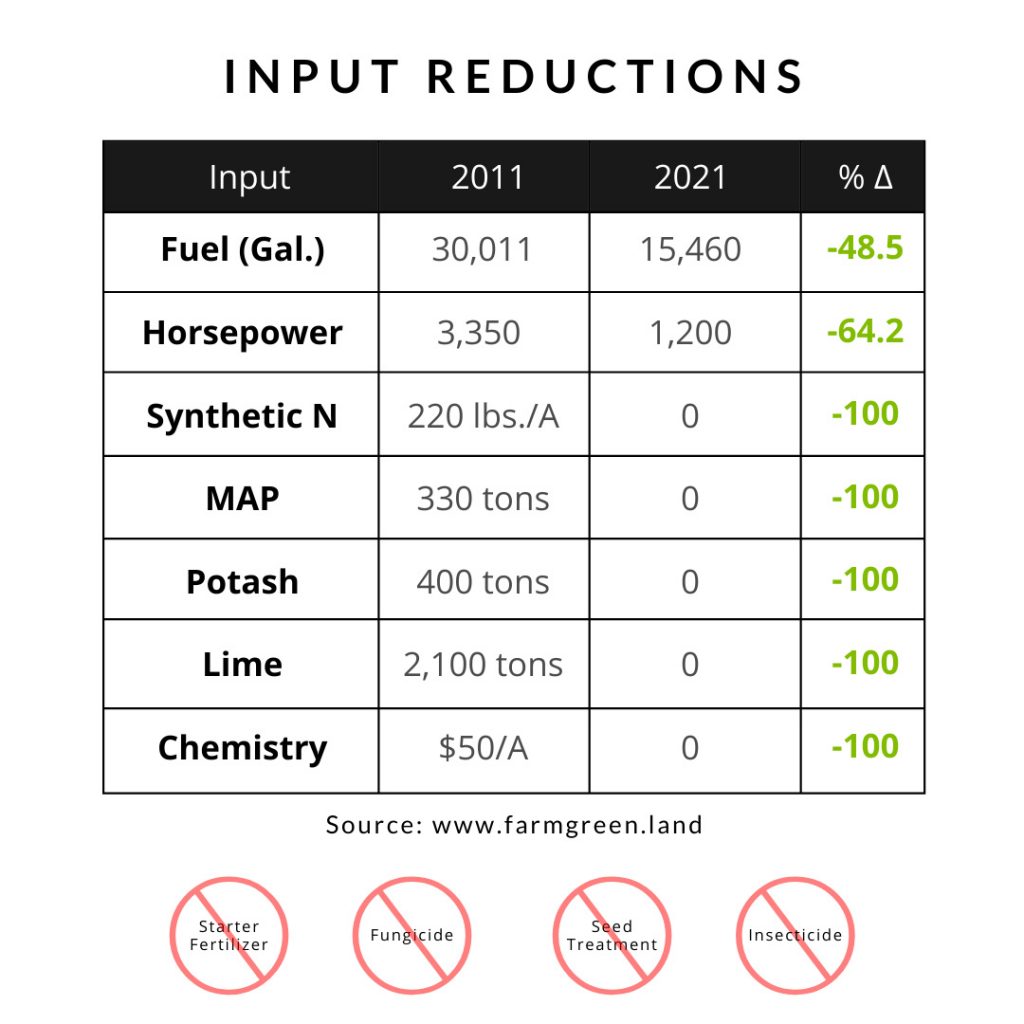

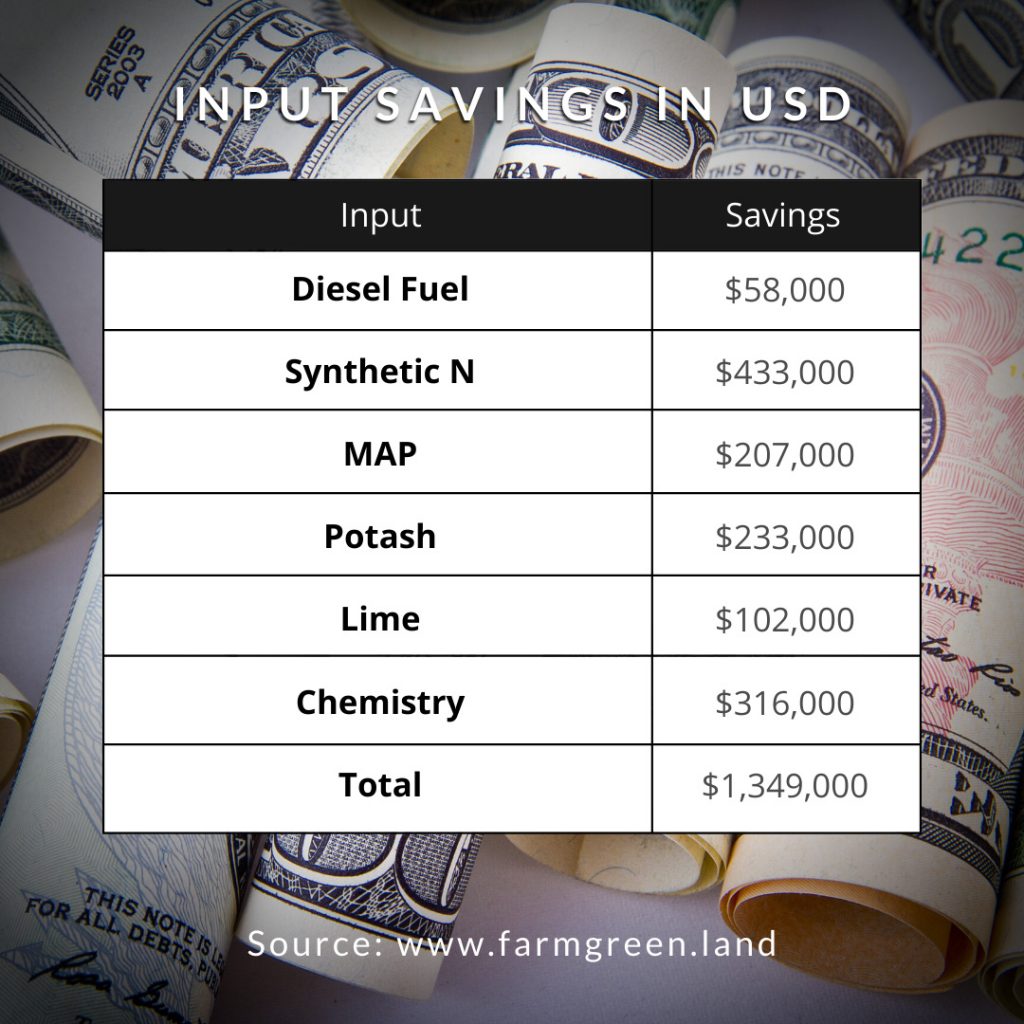

Rick Clark of Clark Land & Cattle in Williamsport, Indiana, can personally attest to the savings from cover crops as part of soil health management. He’s seen his synthetic nitrogen, MAP, lime and potash applications decrease 100%! See his figures below.

Dr. Cappellazzi agrees that it’s a focus on improving soil health—which includes, but is not limited to, cover cropping—that makes the biggest difference to the bottom line. She knows some farmers have increased their net profits by $100 per acre in fertilizer savings with this approach.

She also points out that growers can see financial benefits with their cover crops beyond their fertilizer. Many growers lower their herbicide bills because cover crops effectively suppress weeds. The improvement in soil health leads to more stable yields. And the soil preserves more water in dry years and keeps it moving in wet years, so crops are less susceptible to both drought and flooding.

Cover Crop Seed Quality Makes a Difference

Cover crops’ ability to hold onto nutrients is only as effective as their own success. Seeding a cover crop won’t make a difference if it doesn’t grow.

Unfortunately, in the beginning years of these cost-share programs, we saw a lot of that take place. Farmers opted for cheaper seed, which meant quite a bit was low-quality and didn’t germinate.

Today, cost-share programs require growers to only use quality cover crop seed. If you buy seed with a tag on it, it’s legally required to tell you the germination rate and weed percentage.

“That’s part of the reason why it’s better to buy from a seed company, where their reputation is on the line to sell a quality product, and it has to be tested,” Dr. Cappellazzi says. “I think that diminishes the chance of having big problems.”

You should also try to avoid variety nonspecific (VNS) seed.

“It could be a good form of, say, random clover,” says Dr. Cappellazzi. “But if you have a specific production goal in mind and you have a specific climate or soil type, it’s much more likely to succeed if you have selected a cover crop that’s going to fit in with those specifics.”

Check for Cost-Share Programs to Get Started

Many farmers got their start with cover cropping thanks to cost-share programs. Fortunately, you don’t have to be in the Bay watershed to find similar incentive programs. If you’re interested in cover cropping to preserve the nutrients on your farm, contact your local NRCS office or soil and water conservation district to learn what financial opportunities may be available to help you reap the environmental and economic benefits of cover crops.